*** out of ****

Starring: Thomas Horn, Tom Hanks, Sandra Bullock, Max Von Sydow and Viola Davis

Running time: 128 minutes

Oskar Schell (played by Thomas Horn) is a precocious nine-year-old who is petrified of public transit, rattles a tambourine whenever he is nervous, and would rather communicate with Morse code than pick up a phone.

He is coming-of-age in uptown Manhattan a year after the 9/11 attacks. Oskar calls that tragedy “the worst day” since his father, a jeweller named Thomas (played in flashback by Tom Hanks, loving and lovely), died in the World Trade Center that morning.

However, upon re-entering his dad’s closet, Oskar finds an envelope marked with the word “Black” inside a blue vase. Within that envelope is a key, but Oskar doesn’t know what it opens. The boy believes that finding what the key opens will answer some important questions about his father. Oskar proceeds to track down the 400 or so New Yorkers with the last name “Black” to, ahem, unlock the mystery.

The film version of Jonathan Safran Foer’s 2005 novel, from director Stephen Daldry, arrives in theatres with the same baggage that besieged the best-seller. Many readers intensely admired the novel, while some critics slammed Foer for using the 9/11 tragedy as a plot point.

More streamlined in its transition to the screen – an entire sub-story of tender correspondences between Oskar’s grandparents told in flashback is gone – Daldry’s adaptation succeeds in covering a breadth of emotionally charged terrain with insight and honesty.

The two finest performances in Extremely Loud come from entirely different sources: one newcomer and one recognizable screen veteran.

The new kid is Thomas Horn, in his film debut. As the shelled-up, hypersensitive protagonist, Horn rarely becomes cloying. The idiosyncratic protagonist is a true original, and Horn envelops the character’s quirks to create a steady naturalism. Even with a skinny frame, an unsteadily squeaky voice and beamy eyes, Horn carries the weight of every scene he’s in.

He tackles dense, emotionally shattering material with a quiet fortitude. He perfectly fills the character’s “heavy boots,” a term coined by Safran Foer, and has the dramatic weight to wear them proudly in every frame.

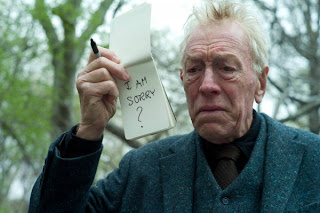

The other actor is Max Von Sydow, who plays the mysterious, unnamed renter who lives across the street from Oskar’s apartment. He accompanies the boy for a few choice excursions around New York City. The renter, however, cannot speak, and has the words “yes” and “no” tattooed into his hands.

Von Sydow’s pantomimed expressions are vivacious, even though the great actor’s face is worn and his baritone one of the most recognizable in cinema.

Beyond that, the film's 9/11 sections are overwrought and kitschy. Images of bodies falling are tasteless while Oskar’s reiterations of the events from that day become forced and mawkish after the first retelling. The book handled these tragic moments with less cacophony.

Thankfully, these sections only comprise about a quarter of the film’s running time. Elsewhere, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close is an often illuminating and deeply moving journey about trying to heal from that aftermath.

No comments:

Post a Comment