10. Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981, dir. Steven Spielberg)

I first watched this film when I was five years old and I often return to that age (in spirit, at least) every time John Williams’ score kicks in. Steven Spielberg’s brawniest and most thrilling entertainment is, first and foremost, escapism as its purest. Mixing in the best parts of old adventure serials with a globe-trotting scope as ambitious as anything the James Bond franchised has ever tried, Raiders of the Lost Ark is the beacon of action filmmaking and also an illustrious peak for one of Hollywood’s greatest screen heroes—Harrison Ford. Oh, and that scene between Indiana and the swordsman is still one of the funniest sequences ever captured on film.

9. Chungking Express (1994, dir. Wong Kar-wai)

No director working anywhere in the world today has their films swim with romance quite like Hong Kong stylist Wong Kar-wai. Honest, passionate and dreamlike, his 1994 masterpiece follows two separate stories told one after the other: both are about cops dealing with recent break-ups while new women dance in and out of their lives. The photography of urban Hong Kong is intoxicating and the performances, especially from Tony Leung and Faye Wong, are terrific. The film breathes with life and a commanding energy, but it’s the raw, subtle nuances between the romantic leads in both stories that feel utterly true. It’s a buoyant journey, and one I’ll be delightful to take again and again.

8. Apocalypse Now (1979, dir. Francis Ford Coppola)

Apocalypse Now could have been one of Hollywood’s biggest flops. During production, several sets were destroyed, director Coppola nearly went bankrupt, actor Martin Sheen nearly died, and plenty of hours of footage made it to the cutting room floor. So, it’s quite a miracle that the film turned out as stellar as it is. Undoubtedly one of the most complex studies of human madness and also a remarkably involving and harrowing war film, it’s a film that pulsates with so much vivid imagery and fiercely haunting performances, it practically recreates the fear, soullessness and destructive nature of the Vietnam War. In terms of recreations of war on film, this one smells like napalm in the morning.

7. Barton Fink (1991, dir. Joel Coen)

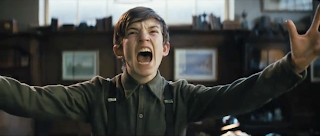

One of the signs of a great film is when one finds new things on every repeat viewing. Two directors, Joel and Ethan Coen, loves to immerse audiences with this treat and pack their films with symbols, metaphors and themes. As terrific as their filmography is, no film is as multi-faceted or as brilliant as their massively under-appreciated 1991 classic. In it, John Turturro plays an uptight New York playwright who moves to Hollywood to work on a boxing film, and ends up, well, wresting with himself. It’s a mix between a hilarious satire and a horror film, and it is an endlessly fascinating trip. Whether you leave the film scratching your head or entirely intrigued, it’s a hard movie to get out of your mind. Maybe another watch will do?

6. 12 Angry Men (1957, dir. Sidney Lumet)

When Sidney Lumet died last April, the motion picture community lost of their finest craftsmen. He was a brilliant actor’s director and made films that felt socially conscious but never self-important. The finest proof of his mastery is his 1957 debut 12 Angry Men, based on a Reginald Rose play. The set-up is simple: 12 jurors discuss, argue and deliberate the facts of a murder trial. It’s more riveting and suspenseful than any courtroom drama has any right to be, and the fact that it develops a dozen fascinating characters in the process (tremendous work from Henry Fonda, Lee J. Cobb and company certainly helps) is testament to Lumet’s genius as a director. Note that the film rarely moves beyond the jury room, yet the visual style never feels rote. It’s a compelling thriller that is composed entirely of dialogue and character development. Those kinds of films are becoming mysteriously hard to find.

5. Memento (2000, dir. Christopher Nolan)

Where was I? Long before he was earning big budgets to make Batman films, Christopher Nolan was primarily known for this brainy neo-noir puzzle about a man (an excellent Guy Pearce) with anterograde amnesia trying to figure out who raped and murdered his wife. The gimmick is that since he can’t remember what’s happened right before, we’re given the details backwards (so we have no prior knowledge of the previous events either). Clever, complex and undeniably compelling, Memento is probably the best example of how to construct a movie in a non-linear fashion. It’s also a fine mystery that may take a few viewings to entirely decipher—but that’s just part of the fun. Ok, so where was I?

4. Almost Famous (2000, dir. Cameron Crowe)

There’s a scene at the beginning of Cameron Crowe’s 2000 rock-and-roll epic where William, the aspiring music journalist, is dismissed as merely a critic by the rock band he is assigned to cover. William then spends the next minute unleashing his intense adoration and enthusiasm for each member of the band. He is a fan first, critic second. I like to approach films in a similar way. That said, this semi-autobiographical film from writer/director Crowe is such an intelligent, exuberant, compassionate, dynamically acted film that every scene feels like its part of a terrific album from decades ago. It’s also one of the best films ever made about music, and one that I will always be happy to give another spin.

3. Se7en (1995, dir. David Fincher)

This film is bloody brilliant, and both of those adjectives can be used equally to describe this grisly detective thriller, arguably David Fincher’s finest achievement. A headstrong rookie (Brad Pitt) and a warm-hearted veteran (Morgan Freeman) are working to track down a serial killer who is murdering victims who have committed one of the seven deadly sins. It’s a frightening journey, filled with twists (courtesy of Andrew Kevin Walker’s cunning plotting) and stomach churns (striking, if lurid visuals come from Fincher’s cold vision). It also features the most spine-tingling finale that I can recall, an ending so devastatingly brilliant that Pitt almost quit the film when studio heads were thinking of replacing it.

2. The Apartment (1960, dir. Billy Wilder)

I already spoke about this one of my Top 10 Comedies list, but it bears repeating: The Apartment is tightly plotted, bruisingly funny and blissfully romantic. Few onscreen couples have had as much zing as the irreplaceable Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine, the former which gives a performance of precise comedic timing and dramatic weight. He plays the owner of a New York apartment, who lends it out to his co-workers and their dates in exchange for a good word and a promotion at his workplace. Lemmon’s balance of humour and pathos is almost as remarkable as the deft way in which director Billy Wilder massages dark themes with light comedy—tone-wise, of course.

1. Magnolia (1999, dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

The world of film buffs is filled with two types of people: those who thought that Magnolia was an overlong, pretentious bore, and those who thought that Magnolia was a magnificent opus of Biblical proportions. I am of the latter variety. It is P.T. Anderson’s masterpiece, an audacious and remarkably acted three-hour journey through one rainy afternoon in the San Fernando Valley. We follow several lonely, troubled souls struggling to find each other—and then the unimaginable happens. Magnolia blooms with big themes, brave ideas and bold methods of storytelling and performance. It’s a film that has grown on me ever since I saw it years ago, and it leaves me spellbound every time I watch it again.